In a recent blog when we introduced the concept of specificity of adaptation, we discussed the benefits of overtraining. It’s also important to understand the balance here, where overtraining is necessary to a point but training too much is counterproductive.

Specificity is the idea that the body responds and adapts directly to its inputs and environment. So how does this affect performance? If an athlete continues to train in a state of excessive fatigue where performance declines, the body will adapt to that level of diminished performance over time.

Imagine, for example, a soccer player doing a series of sprints with the goal of increasing their speed. When they reach the point of fatigue, their form breaks down, and they lose speed.

If they continue to sprint with poor form or reduced speed, this is exactly how their body will learn to move. There may be an adaptation in terms of endurance since their body will adjust to the specific demand of running at slower speeds for longer periods of time. Over time, however, the same drill done to increase their speed can end up slowing them down.

How to Determine the Optimal Level of Training

How do athletes know whether they’re training too much or too little? How can they determine the optimal amount of training they need to support peak performance? There are two ways:

- Measuring performance during training sessions

- Monitoring the effects of training on health in the hours and days after a workout

During a training session, the key for any athlete is to maintain a certain level of performance. If they go below that performance threshold at any point during training, they need to rest until they can return to that level—or stop the session and start recovering.

For example, if an athlete is working on speed or power, we may want to use their vertical jump as a performance indicator during the session. If they can jump thirty inches, and we’re trying to stay within a 10 percent range of overtraining, we would continue to retest their vertical jump and stop training if it dips below that 10 percent threshold (i.e., if they can’t jump at least twenty-seven inches).

Besides measuring performance during training sessions, there are indicators of nervous system health that help us gauge whether an athlete is getting the right amount of training. Using these indicators to evaluate the body’s response to workouts is a helpful tool to assess whether training is stimulating enough to trigger positive neurological adaptations. These indicators measure performance itself (i.e., whether performance improves throughout training) and the underlying health of the body (i.e., how well the body is meeting the demands of training and daily life).

If an athlete has low heart rate variability or suffers from frequent upper respiratory infections, for example, these are indicators that they’re not recovering effectively from training. Most likely, they have too many stress hormones circulating in the body, which can lead to diminished performance and health problems over time. Poor sleep quality, digestive problems, and low energy are also indicators that the body is having trouble keeping up with the challenges of training.

Now let’s look at a model for building towards and maintaining an elite level of performance. There’s a natural hierarchy of performance that we refer to as “The Performance Pyramid” and it represents a structured approach to training.

The Performance Pyramid

Though the specific components of an optimal training program vary from athlete to athlete, the building blocks of elite performance are basically the same.

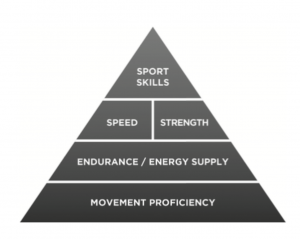

At NeuFit®, these building blocks form what we call the performance pyramid:

At the base, or level one, of the pyramid is basic movement proficiency, which includes things like balanced muscle activation, proficiency in foundational movement patterns, and appropriate range of motion in all the joints.

Level two of the pyramid is endurance and energy systems (also known as “work capacity”), which includes having a healthy metabolic system to generate the energy needed for training and recovery.

Strength and speed are at the third level. At the top of the pyramid are sport-specific skills.

Why do we approach performance training this way?

The idea is that until athletes build a strong foundation in terms of movement, endurance, strength, and speed, their ability to improve their sport-specific skills will be limited.

In short, if an athlete goes straight to the top of the pyramid without laying the groundwork for their skills, the pyramid topples over. Sooner or later, their performance diminishes and/or they get injured.

Likewise, if an athlete only trains in one or two of the essential elements of performance, they not only reduce their chances of competing to the best of their ability, but they also limit their chances of remaining competitive over time.

While it’s important to work all the levels of the performance pyramid, the principle of specificity also dictates that different athletes need a different balance of these foundational components. In other words, we need to structure training so that it’s relevant and appropriate to an athlete’s sport.

Let’s charge forward (and up the Performance Pyramid) to better outcomes together!